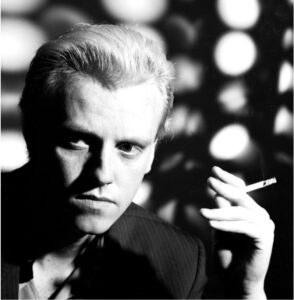

As Muslims travel to Mecca in pilgrimage, in 2002, during a short stay in Manchester, I visited Sheffield, a city that even if I would never describe as beautiful, was the place where some of my favorite albums were made. One of the bands that put this industrial city in the musical map was Heaven 17, composers of some classics from the 80s. We have talked with Glenn Gregory about the beginnings of the band that will be playing at W-Fest next Sunday 28th of August in the Belgian city of Ostend.

—Glenn, you were in a punk band called Musical Vomit. Was that your first band? That’s where you met Martyn, right? When was this?

—Glenn, you were in a punk band called Musical Vomit. Was that your first band? That’s where you met Martyn, right? When was this?

—Musical Vomit, was my first ever band. It was initially formed by a guy called Marc Civico and Ian Craig Marsh (later of the Human League and Heaven 17). I think they did a couple of performances as a duo and then were joined by myself (bass guitar), Nick Dawson (drums), Paul Bower (guitar) and Ian Reddington (bv’s). We were also occasionally joined by Mal Veal (saxophone), he went by the name of Captain Zapp and played the entire gig inside a Hessian box with arm holes cut out so he could hold the sax!… In fact, all you could see was two arms holding a saxophone. The name Musical Vomit came from a music papers review of the band Suicide and seemed apt for the band that we were to become.

We weren’t really a Punk band, as it predated punk by a few years but in ethos and action I suppose we were pretty Punk. It was a kind of mix between The New York Dolls, Alice Cooper and a biker gang. With such song titles as “I Was A Teenage Necrophiliac,” we were never really heading for chart success. I think it was toward the end of Musical Vomit that Martyn appeared on the scene. He was introduced to us by Paul Bower and we all got on really well and started planning new musical enterprises.

—After that you were in VDK and the Studs with members of Cabaret Voltaire (can you please tell us who they were), Paul Bower, Adi Newton and the rest of what later became Heaven 17. I read that it was a kind of collective. Can you please tell us more about this?

—After Musical Vomit, came a host of short lived sometimes completely imaginary bands, most only ever played one or two performances. The last of these “pop up bands” was a crazy conglomeration of a few of the more esoteric people that we were hanging around Sheffield with. I suppose this was maybe around 1977… We were called VDK and the Studs. By this time I had given up the bass guitar and become the singer. “The Studs’ had become known in Sheffield before we had ever even rehearsed as we had printed lots of posters and stickers proclaiming VDK and The Studs‘ new single out now. We had plastered these all over the city center, especially around the record shops. We even had Studs new single SOLD OUT posters which we put up in record shops…

We created such a buzz that we were asked to support a punk band called The Drones at a gig in Sheffield. So with the gig in place we had our first ever rehearsal. The band line up was Richard and Mal from Cabaret Voltaire, Adi Newton from Clock DVA, Paul Bower and Hayden Boyes Weston from 2.3 and myself Martyn and Ian… It was scarily bad, in fact, so bad it was almost good, we played the gig after one rehearsal and the absolute cacophony of noise that came from the stage was terrifying, a completely mad unholy mix of synths, guitars and voices all doing something largely unconnected yet almost came together…almost! The gig ended with us refusing to leave the stage, The Drones manager and roadies were trying to drag us off but we just wouldn’t leave, we were playing an impromptu electronic version of the theme from Doctor Who, which became a chant of “The Drones wanna come on now”… ahh the heady days of electronic punk pirates.

There was a rumour that persisted for decades that someone had recorded that iconic insane gig. I always  believed it to be untrue… until one day only a couple of years ago, in a club in Germany someone came up to me and asked me to sign a reel to reel tape box. It was old and falling apart and written on the front in said: “The studs”. It was the recording of that gig! I ran backstage to Martyn ranting as if I’d found The Holy Grail. I arranged to get the tape digitised and sent to me. To this day I have only ever listened to the first 2 minutes… its dreadful and scary, and no you can’t hear it!

believed it to be untrue… until one day only a couple of years ago, in a club in Germany someone came up to me and asked me to sign a reel to reel tape box. It was old and falling apart and written on the front in said: “The studs”. It was the recording of that gig! I ran backstage to Martyn ranting as if I’d found The Holy Grail. I arranged to get the tape digitised and sent to me. To this day I have only ever listened to the first 2 minutes… its dreadful and scary, and no you can’t hear it!

It was after this gig but not because of the gig… that I decided it was time for me to move out of Sheffield. I had always taken photographs and wanted to move to London to become a “Rock Band” photographer. So after a fantastic weekend-long party, that’s what I did.

—You were going to be the singer of The Future but it did not happen because you moved to London, right? Did you follow the music of this band when you were in Sheffield? The material of this short-live band has been released a few times, the last one as part of the Clock DVA box set. Did you see them or were interested in their music at the time?

—At this time, Martyn and Ian had been working on some new music with Adi, (pre Clock DVA, pre Human League). It was purely electronic and beautifully dark, they recorded quite a few songs, in fact, The Future began to cross over really and some of the backing tracks became Human League‘s songs.

I always remained close to Sheffield and the music. In truth I would hitchhike back at least a couple of times a month to see everyone, and when The Human League had formed for real, I was there as an early photographer at a lot of the gigs, I even took a front cover shot of them for Sounds Magazine. Also whenever the band travelled south for gigs, they would all stay at my tiny grotty flat just off Ladbroke Grove in London.

It was because of a music photography job that I ended up in Sheffield, coincidentally on the same day the The Human League had had there big “Split” meeting, I’d called Martyn and asked if he wanted to meet in town for a beer before I had to go and take shots of Joe Jackson live at the Sheffield City Hall for the NME. He said he did and that he had something to tell me. We met in a pub called the Red Lion behind the City Hall venue, we ordered a couple of beers and he proceeded to tell me that The Human League had split and he and Ian were going to form a new band. After a few more pints he started to ask me questions about London and was I happy down there, eventually saying why don’t you move back up here and the three of us can start a new band… That was Friday, I went back to London on Saturday and by Monday I was in Sheffield again, we had started writing as Heaven 17. Well, there were a couple of other names in the hat at that point but thankfully Heaven 17 won… 5 days later we had written and recorded Fascist Groove Thang.

It was because of a music photography job that I ended up in Sheffield, coincidentally on the same day the The Human League had had there big “Split” meeting, I’d called Martyn and asked if he wanted to meet in town for a beer before I had to go and take shots of Joe Jackson live at the Sheffield City Hall for the NME. He said he did and that he had something to tell me. We met in a pub called the Red Lion behind the City Hall venue, we ordered a couple of beers and he proceeded to tell me that The Human League had split and he and Ian were going to form a new band. After a few more pints he started to ask me questions about London and was I happy down there, eventually saying why don’t you move back up here and the three of us can start a new band… That was Friday, I went back to London on Saturday and by Monday I was in Sheffield again, we had started writing as Heaven 17. Well, there were a couple of other names in the hat at that point but thankfully Heaven 17 won… 5 days later we had written and recorded Fascist Groove Thang.

Going back to Sheffield to form Heaven 17 was great fun, Martyn, Ian and I have always had a very similar taste in music, we always loved experimental musicians but also loved dance music, disco, funk, glam and pop, even film soundtracks, I suppose Heaven 17’s “sound” comes from those eclectic tastes.

—How do you remember the Sheffield of that time?

—Sheffield was a great city to be during the early 80s. There were a couple of really good clubs and some fantastic bands like the Cabs and Vice Versa, who became ABC around and we often meet in pubs and clubs and Cabaret Voltaire used to have brilliant parties.

—Is it true that both Penthouse and Pavement and Dare were recorded in the same studio?

—The only asset that The Human League had when they split was a recording studio. I use the word studio in its broadest sense, it was really a derelict 5 story building with one floor equipped with questionable recording equipment and no windows… But neither of the parties wanted to give it up, so we agreed to share the place. The Human League would work from 10AM to 10PM and we would record on the night shift from 10PM to 10AM. It’s still hard to believe that both Dare and Penthouse were written and recorded in that studio… at the same time.

—You were you involved in the creation of the British Electric Foundation, right? Or in the recording of the first album? You sang in the second album, right?

—BEF and Heaven 17 were actually formed at the same time. After the split Martyn and Ian didn’t really want to be caught up with the ‘Album Tour, Album Tour” spiral. We looked at is as old-fashioned and wanted to break free of that way of doing things. So they decided not to sign to Virgin Records as a band, but as a production company, a label within a label, I know that’s really normal now, but at the time it wasn’t at all. In fact, the original idea was that Heaven 17 would be signed to BEF, an album released then BEF would release another band… The fact, though, was that we all loved being in a band together again and Heaven 17 quickly became the three of us as a band and success was quick to follow…

—”(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang” was banned in the UK because of the reference to Reagan, but what happened with this song in the United States? I did not find any release of the single in the USA.

—”(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang” was banned in the UK because of the reference to Reagan, but what happened with this song in the United States? I did not find any release of the single in the USA.

—Well, it was all going beautifully with “Fascist Groove thang” getting massive critical and fan acclaim only to be stopped in its tracks by the BBfuckingC deciding that they were going to ban it, for its overtly political content… So it’s chart success was halted, but it has stood the test of time and unfortunately is just as relevant today as it was when we wrote it. It never did get an American release… strange that! Maybe there’s still time?!

—The band has always tried to show the horror of capitalism and consumerism wrapped in a perfect pop form. Do you think that the audience always got the idea or people were thinking that you were some kind of yuppies?

—We were very interested in writing lyrics with a serious message or intention, but loved hiding that message or slogan within a ‘pop” format. I think we believed people would get the idea, although unfortunately some people did seem to miss the irony of the Penthouse and Pavement album and jumped on the look and style as a kind of approval to be yuppies! But there’s only so much you can do to illuminate the unilluminated.

Whether or not people listen to our ”message” is beyond our control. But it makes it interesting and relevant for us, and years down the road when someone comes up to you and explains that your song and or lyric meant a lot to them, it is an amazing feeling.

—I was reading about the vocal arrangements of Luxury Gap and was really surprised by some of the details: “The opening vocal on Let Me Go, for example, has 118 multitracked voices singing in 14-part harmony.” That’s quite amazing. Being the singer, how much involved were you in all this? Why did you want to achieve such complexity?

—I loved recording all the vocal arrangements, Martyn and I would spend hours in the studio singing hundreds of harmonies multitracking each harmony seven times. It was about creating a sound and it didn’t matter that you couldn’t hear all those tracks, it mattered that it just sounded just exactly that way. “Let Me Go”, for instance, would not have been the same song had we not done so much work on the vocals. I still love singing that song live… I get lost in it.

We had made a conscious decision to make these songs more polished/ produced than the first album and we certainly went for it, whether it was recording massively complex and multi, multi, multi-tracked vocals or a seventy-piece orchestra or getting the Earth Wind and Fire horn section, The Phoenix Horns to play on the tracks. We had a ball, it was so much fun and, it cost soooo much money… I think it took us years to pay it back, but we loved the result and so did everyone that listened to it.

—In How Men Are you try to express the nuclear holocaust fear of the time, something than even now, we can feel. Do you think that a pop record can help make people more conscious of the problems of the day?

—We recorded How Men Are in the same studios as The Luxury Gap, but wanted a cold a more austere sound. I think we were still afraid the world would end with a big bang. Actually, I’m still worried about that… We write what we feel strongly about and I think that fear and angst filtered through very much on this album.

—During the first years, you hardly played live. Why?

—In all this time we hadn’t played live, we’d been asked to. In fact, we’d been offered a lot of money to do so, but we had made a decision all the way back at the beginning that playing live just seemed old fashioned… MTV had started about the same time that we had, and making videos to promote your songs just seemed a more futuristic way to do things… Obviously, we were quite probably wrong, but were stubborn fuckers and it took a few decades for us to realise that fact, but we are doing it now and we absolutely love it. I wonder if we’d be enjoying so much now, if we’d played live back in the day.

—With the previous album and with Pleasure One, the band started using more and more acoustic instrument and session players, moving towards a more traditional sound. Was this a deliberate movement to sound more on the radio or the band just tried to find a different sound?

—Pleasure One was a further departure from synthesiser. Maybe we were heading to a more a traditional sound because the synth had become a little boring and predictable or we were trying to sound more like the older dance/ funk songs that we listened to. It’s not a favourite record of mine.

—In Bigger Than America, the band tried to use old synths. Now that there is a kind of “back to analogue” tendency , do you think it could have been more successful if it had been released now?

—Oddly enough, when we did come back to writing again it was for the album Bigger than America and we had been inspired to write these songs by reimagining what our second album could have been… By that I mean instead of following a path of a more complex and bigger production including the use of orchestra etc we had carried on a more electronic path, which was an interesting though for us and it is an album I like a lot… It’s the alternative second Heaven 17 album.

—What can you tell us about your career in soundtracks? I always read that Heaven 17 was influenced by Ennio Morricone, was this influence coming from you?

—Having always listened to soundtrack albums, I jumped at the chance to score a short film for a new director, and now 20 years later, it’s how I spend most of my time. I really love writing music to picture, it calls for a totally new way of thinking and I get to write music I would have never gotten near to were it not for scoring. It’s a passion which I adore.

—You have also recorded an album as Afterhere with Berenice Scott. What can you please tell us about this? She is also part of Heaven 17, right?

—I write in partnership with Berenice Scott as Afterhere. As well as writing for film and TV we have released an album called Addict.

She’s away touring with Simple Minds at the moment, but she’ll be back later this year, when we will start our new film project.

Then hopefully a new Afterhere album.

—What can we expect of the future of Heaven 17? Any chance of a new album?

—And, of course, talking about new albums…

Will there ever be a new Heaven 17 album?

The answer to that is perhaps… We need to be inspired and not busy doing other things… Although at the moment, I’d say the odds are in favour rather than against, there are things hanging around that we both like and a few finished (almost) tracks that could be a start…

But in the meantime, we will be playing live at W-fest, for our third time. It’s something we really enjoy doing, we have yet to decide on the set, but we were talking about maybe doing a couple of early Human League songs just for synthetic fun.