Industrial pioneers, Test Dept have proved that it’s possible to have a coherent career, both musically and politically. They have managed to keep surprising us, during all these years, on record and also on stage. We have talked with the band who has added some extracts from Total State Machine to the interview, which will help contextualise their incredible trajectory. They are one of the bands that you should not miss at DarkMad.

—I read that all the members of the band were unemployed just before founding Test Dept. How was living in the UK at the beginnings of the 80s?

—I read that all the members of the band were unemployed just before founding Test Dept. How was living in the UK at the beginnings of the 80s?

—Paul Jamrozy: We came from different parts of Britain and settled in New Cross, which was a very run-down area, lots of the properties and businesses around us were boarded up, there were lots of squats and it was here that Test Dept lived and worked. The community was a multicultural mix of students and the unemployed. Musically the punk scene had dissipated, but the experimentation of post punk had changed the sonic environment. Music was a vital force that provided a focus and an antidote to the oppression that existed.

In the political landscape, Thatcher was elected in 1979, it wasn’t long before she took Britain into war in the Falkland Islands and rallied the country around a jingoistic message, raising her popularity before the coming election. Her special relationship with US President Ronald Reagan was to open the doors to the neoliberal economy with its shock doctrine tactics, which were to soon take effect. Resistance culture arose as a counter-force and Test Dept took to the barricades.

—More than a decade ago, I visited Sheffield to try to understand how industrial music “started” there. And I thought that the endless sound of factories were the key in the creation of the style. How do you think that living in the docks of South London helped the development of the sound of the band?

—Graham Cunnington: We relocated to the docklands of South London where we were surrounded by the inevitable consequence of Thatcher’s destruction of the heavy industry and manufacturing economic base in favour of a service economy. Corrugated sheeting, empty beer barrels, gas cylinders, car springs, they were everywhere around us. Deptford Creekside was our playground, we wandered around the old decaying factories, rummaged on the banks of the Thames and scavenged in the scrapyards that proliferated in the area.

—The band used unconventional instruments such as scrap metal and industrial machinery as sound sources. Were Einstürzende Neubauten an inspiration or both bands just did the same at the same time?

—Paul Jamrozy: I saw EN in Berlin, they were like a wrecking ball to mainstream rock music. These were ideals we shared in our fledgling state. ’Steh auf Berlin’ struck a chord. It was a clarion call to stand up and fight and seemed to embody what was happening in Europe at the time.

—Graham Cunnington: We were on the same label as them (Some Bizzare). They played metal percussion. That’s where the comparison ends for us. They were very creative and somewhat groundbreaking, with their use of sound, especially in those early years, but they seemed to be working more within the whole “rock” aesthetic which was not our scene at all.

—Paul Jamrozy: In our book “Total State Machine,” Jani from Laibach compares various groups from that era and he likened EN to Velvet Underground. I thought that was quite an astute observation.

—History, (the strength of metal in motion) was released in 1982, and it’s the band’s first cassette, published to celebrate the first year of the band, right? How was that first year?

—From the play Pain by Graham Cunnington: We started rehearsing in a dark dank cellar lit by candlelight. Our instruments: a dustbin from outside, corrugated iron ripped from a fence, a water tank found on waste ground, a couple of petrol tanks from a rag and bone man (Scrap dealer with horse and cart), scrap pieces of bent metal from an abandoned factory, and the inner frame of an old piano with strings stretched dangerously taut. We began drumming, hour after hour, day after day. An unbelievable, demented din, driving the neighbours mad, bringing the police to the door. We played on, driving through the pain, focusing our anger, intoxicated by the beats. The rhythms binding us together, creating one voice, fuelled by the power in our hands, building our own future. Transforming the anger into something positive. No sense of self. Pure, guided energy. Generating more power together than we could alone; us against the world. I can feel my hands, wrists, elbows and shoulders unknotting. Sticks flying faster than I can see. New rhythms firing out of me. Blood and sweat driving the demons away. Finding peace in extremity. A silent place in the heart of the storm.

—In Ecstasy under duress, there are some of the first live recordings of the band, some of them from illegal events. How was the atmosphere in these first concerts? The band was even arrested, right?

— From TSM: Titan Arch November Reprisal was in Titan Arch Nº. 12 in Waterloo. A huge arch running off from a central tunnel under the railway lines coming from the main hub of Waterloo Station, just south of the river in London. The name became pretty ironic due to the full-scale police raid on the night. It was billed as a secret location and was hard to find so we spray-painted our name with arrows from the Cut at Waterloo all the way to the site – the directions were still up in Great Suffolk Street 20 years later. The ticket had a map on the back to indicate the location. The address wasn’t advertised in any of the press but considering the number of police that were there they knew about everything in advance. They were militaristic in the way they just burst through the entrance in straight lines and squared everything off isolating the audience into small groups. There were at least 3 Special Patrol Group vans alongside the normal police.

We had done the soundcheck and were standing on a walkway looking down on the crowd of 1200 or more who were already inside (including plain clothes police too, one in denim with a pink Mohican). We had old megaphone speakers running along either side down the length of the huge railway arch, one blaring out Voice of America and the other Radio Moscow. Then the police came in with one megaphone, which seemed a bit puny compared with our rows of them. A voice shouted: “-This is a police raid,” the excitement was tangible and some people thought it was part of the event. Then they flooded into the space en masse and surrounded everyone, took their names and addresses. They wouldn’t allow anyone to leave until they’d been “processed.” We were all arrested and taken to cells in Southwark police station. There were many questions. Roy Hanney who drove and helped us was arrested for “belligerence to police officers.”

We had done the soundcheck and were standing on a walkway looking down on the crowd of 1200 or more who were already inside (including plain clothes police too, one in denim with a pink Mohican). We had old megaphone speakers running along either side down the length of the huge railway arch, one blaring out Voice of America and the other Radio Moscow. Then the police came in with one megaphone, which seemed a bit puny compared with our rows of them. A voice shouted: “-This is a police raid,” the excitement was tangible and some people thought it was part of the event. Then they flooded into the space en masse and surrounded everyone, took their names and addresses. They wouldn’t allow anyone to leave until they’d been “processed.” We were all arrested and taken to cells in Southwark police station. There were many questions. Roy Hanney who drove and helped us was arrested for “belligerence to police officers.”

Marc Almond was arrested for being on the front door with loads of cash in his pockets. We were thoroughly boisterous in the cells, singing throughout the night till they booted us out onto the street at 4.30a.m. in the morning with no way of getting home as they had impounded the van along with our equipment, all the construction materials inside the arch and the cash from the door. We were never charged and we eventually got our equipment back. We did the replacement night at Heaven charging 75p. It was a phenomenal occasion, the perfect antidote to the events at Titan Arch.

—What’s the concept behind the Ministry of Power? It’s also the name of your label, right?

— From TSM: MOP was an expansion of TD into a production vehicle incorporating creative collaborators in large-scale live works. It originated at The Unacceptable Face of Freedom, a seminal site-responsive event at Paddington, and further monumental multidisciplinary performances. We developed the idea further with some indisposed volunteers when we represented Britain at Vancouver’s World EXPO “86 supported by the Queens Own Regimental Band on the day Prime Minister Thatcher paid a visit. Demonomania, a Boschian nightmare incorporating a ritualistic purging of the Monasterio de San Benito in Valladolid – the birthplace of Torquemada, Inquisitor General of the Spanish Inquisition was a further collaborate with local performers and musicians from the city. We have always been interested in working in a collective sense and the collaborations have been an extension of this approach. Our work with artists as diverse as Brith Gof, Diamanda Galas and Alan Sutcliffe (Kent NUM – from the mining community) have given us enriching experiences and created some of our finest moments. We find the investment and expansion of new ideas that derive from collaborative practice an inspiring and transforming experience and we look forward to future possibilities in this direction.

—Being Spaniard, I am curious about your show at the Monasterio de San Benito that you have just mentioned. Can you please tell us more about this?

—Paul Jamrozy: Back in the 1980s there were some exciting performance groups emerging from Europe, like La Fura del Baus and Archaos. Their work was close in spirit to the events MOP was putting on. The ‘Festival Internacional de Teatro y Artes de Calle’ in Spain offered us the chance to stage an event at an old monastery in Valladolid. We started doing some homework. We filmed some Catholic Easter processions, and recorded the traditional drum rhythms and local bagpipes. We watched Buñuel’s documentary film about the villagers in Calanda drumming all day & night until their hands bled. We read about the Inquisition, the Spanish Civil War, and Franco – whose dictatorship had only recently ended. In our imaginations the shell of this old monastery resonated with past events and atrocities, linked to fascism, religious intolerance & anti-Semitism. With Demonomania we tried in our own way to exorcise these demons.

—Brett Turnbull (TSM): The performance was named Demonomania and Bosch’s paintings of hell were used as a key reference, with giant musical instruments that doubled as instruments of torture. The action grew largely out of studying techniques the Inquisition developed to manipulate public hysteria during witch-hunts.

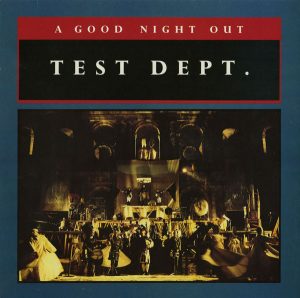

For the projections Brett Turnbull photographed the ghost town of Belchite, abandoned after the Civil War and left untouched as an eerie monument in the Spanish desert. The iconic image of the show was of a dictator or as Oscar Wilde’s ‘Dorian Gray,’ a decomposing portrait that reflected internalised evil, like staring into the corrupt soul of a fascist leader. The image of the stage in the Monasterio became the cover for the album a Good Night Out.

—What can you tell us of the collaboration with the South Wales Striking Miners Choir that was the origin of the Shoulder-to-Shoulder record? The band toured and made this album in support of a miner’s strike, right?

—What can you tell us of the collaboration with the South Wales Striking Miners Choir that was the origin of the Shoulder-to-Shoulder record? The band toured and made this album in support of a miner’s strike, right?

—Graham Cunnington: The Miners” Strike resonated with us then and now, and is still relevant as marking the moment when the post-war liberal consensus finally started to be fully broken apart; when the uninhibited neoliberal free-market economy could be fully implemented. The Miners’ Strike was the pivotal campaign in the UK, the last great resistance to the introduction of the system of individual and corporate greed which has led, over the subsequent years, to today’s political, social and environmental mess. Thatcher knew if she could break the miners, she could break the unions and thereafter allow the implementation of corporate hegemony and diminished workers’ rights. This model subsequently spread across much of the globe.

—From Angus Farquhar’s Diary – TSM: There is an untold power in mixing together two music’s of such seemingly diverse backgrounds. An alchemy of possibilities, of confusion and truth that leads to new patterns and a widening of horizons. Those who listen to the choir cannot do so without further appreciating the roots of their struggle. A historical background becomes present with unchanged relevance. Test Dept should not be relegated to the fringes of the avant-garde, neither to the cheap battlefield of the pop/rock arena. Genuine achievement comes from presenting what is happening in front of people’s eyes, in a way that abandons the formulas of easy assimilation. Here is a truth shown in a brutal and harsh light – a reverse interrogation.

—Beating the Retreat is considered the band’s best work. Do you agree? Why do you think that fans prefer the band’s third album?

—Beating the Retreat is considered the band’s best work. Do you agree? Why do you think that fans prefer the band’s third album?

—Paul Jamrozy: Actually our first vinyl album. It was a huge sonic development from our previous rough and ready sound aided by the genius producer Ken Thomas. We always treated the studio very differently to live shows, where that raw sound and energy was not something that could be easily captured. It has some strong material on it that is recognized as significant of the early industrial scene.

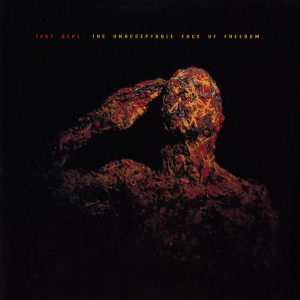

—Graham Cunnington: I would say that The Unacceptable Face of Freedom was up there too, but our catalogue covers such a wide range and different fans like different periods, and albums.

—Paul Jamrozy: For Disturbance and the current work we have revisited our archive and sought to capture that early energy and rawness combined with contemporary production values. I think we have always tried to do something different in recordings, we have not been interested in repeating a formula, we have shown diversity in working with many different artists and with a variety of styles from classical to techno. Of course, it is all highly subjective.

—Why did the band stop working with Some Bizarre after this album?

—Paul Jamrozy: To give them due credit, Some Bizzare were responsible for bringing many of the best experimental and alternative acts under one roof and were almost untouchable for a long period. All these acts were very different but shared a sense of creative adventure that is rare. We were always fiercely independent while recognising that which we had in common with bands like Neubauten, Laibach and others, which was largely our sense of being European in the midst of the cold war. The label had its time but imploded possibly from being over ambitious and not taking care of the day-to-day business and keeping its artists happy.

—Like some other records, The Unacceptable face of freedom shares the name of the album with some events that happened at the time. Was this album created with the music played there? It was a collaboration with Malcolm Poynter, right?

—Like some other records, The Unacceptable face of freedom shares the name of the album with some events that happened at the time. Was this album created with the music played there? It was a collaboration with Malcolm Poynter, right?

—Paul Jamrozy: It was a meeting of minds with South London sculptor Malcolm Poynter whose work emblazoned the iconic Unacceptable Face of Freedom album cover. We saw his work and immediately saw the connection. We met up with him and he was really open to collaborate, he loved the energy and anger of the music and allowed us to create images of his work for the cover and to use as visuals for a live performance. At the time of the album, we produced the UFoF show at Paddington the first Ministry of Power collaborative event working with dancers, poets, circus performers, metal sculptors, militant miners and Malcolm with his sculptures in the space as part of the performance and projected on film.

— From TSM: The approach to making this work was as a political response and in direct cultural opposition to the rise of Thatcherism. With the Ministry of Power, Test Dept looked to expand the scale of live shows, requiring a great degree of collaboration between the various elements. The stunning location required bespoke staging and understanding of audience movement to instinctively combine a number of disparate art forms into a greater whole to deliver a unified aesthetic for this seminal large-scale event.

—The band has paid special attention to the visual part of their shows. For you, when has the band achieved the best match between image/sound?

— From TSM: Today, we are working with Austrian artist David Altweger who has a very original and unique style which is both abstract and narrative driven, highly political and audio reactive which makes it part of a total experience. Visuals have always been an integral part of our performance from the early days with Brett Turnbull and a more constructivist style influenced by the Soviet avant-garde filmmakers Vertov and Eisenstein but with a very British feel.

He used the decline of physical work in Britain and juxtaposed this with an ironic use of the Stakhanovite (heroic worker) image. We were surrounded by miles of empty factories, docks and pure wasteland in south London. Britain as a manufacturing power was falling apart, our vision was to comment and reflect that decline, valuing that which was least valued within the capitalist system, doing something positive with very little, a through line from the whole punk DIY ethos.

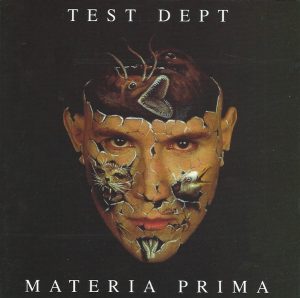

—Materia Prima is a more atmospheric album. Is it because it’s music for a dance group?  How were the concerts of this tour, the groups were dancing to the music of the band? Did the band work with choreographers?

How were the concerts of this tour, the groups were dancing to the music of the band? Did the band work with choreographers?

—AF and PJ: Yes, Materia Prima was a soundtrack to a collaboration between Test Dept and the Rotterdam Dance Company, which toured in the Netherlands. Unfortunately, it became a clash of ideas between the choreographer and us; from creating from a point of abstraction, or the narrative being anchored by our more ideologically driven approach (the dancers should drum, we should dance, inverting interdisciplinary stereotypes). Our hopes were high; this was to be a new dance/music performance utilising ideas of elemental public ritual, a bold attempt to recapture the spirit of pre-Christian rites. However collaboration is difficult and on this occasion it never quite worked out.

—Pax Britannica was another interesting album, based on a score by John Eacott (he was also playing in the previous records, right?) and featuring the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. It’s the closest that Test Dept would go to classic music. Was the band more interested in this kind of music at the time or was it the music that fitted better the Second Coming event?

—Paul Jamrozy: We had always been interested in classical music and our use of elements from composers such as Gorecki, Shostakovich and Prokofiev was part of our performance from the very beginning. What was to finally culminate in the album Pax Britannica started its journey as the live track “Empire” for the Unacceptable Face of Freedom event at Paddington in 1986. The track became a major feature of the shifting TD live set throughout the late eighties, evolving into a Brechtian styled theatrical piece with various adaptions and incarnations scaled up for larger events including Expo “86, Siege of Wapping and the Doulton Fountain Project. It was finally laid to rest as its themes morphed into the Second Coming in 1990, with a targeted critique of the heritage industry and the fictitious use of the past to promote right-wing ideology. A warning of the coming of the current political climate of autocratic fascistic populists.

—Second Coming” event programme: The past is always a created ideology with a purpose, designed to control individuals or motivate societies, or inspire classes. Nothing has been so corruptly used as concepts of the past. …The past has only served the few; perhaps history may serve the multitude.

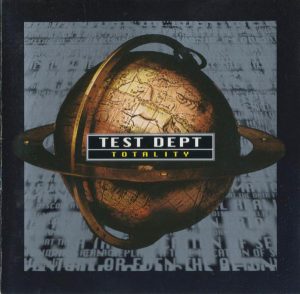

—Instead, the band last albums from the last century, Totality and Tactics for Evolution were more proper albums, I mean that they were not based on live recordings or collaborations. Why did the band change their method of working?

—Instead, the band last albums from the last century, Totality and Tactics for Evolution were more proper albums, I mean that they were not based on live recordings or collaborations. Why did the band change their method of working?

—Paul Jamrozy: Technology changes the means of production, these albums are of a different period and have a different feel, you could say more technological. But we would regard these albums as an accurate reflection of those times, where technological change had a huge influence on all music. TD has always created sound that reflects the environment we live in and the world as we see it. Totality has a lot of global references African, Middle Eastern, Asian,”Woza Moya Woza (Come Spirit Come)”, “Al’ Rabih (The Spring)”, “Zazen” and there are more abstract and ambient pieces like “Red Dust” with Katie Jane Garside’s incredible contribution. We consider Totality a strong album. Tactics was more difficult, in some ways incomplete, we had issues with KK records and they put it out when it was not really finished from our perspective. However it has some good moments and reflects that time which was the end of an era and of TD in that formation, working in a certain way.

—In both albums there is an influence of modern electronic dance music, like drum n’ bass and breakbeat. Was the band interested in this kind of music?

—Paul Jamrozy: Our nucleus was engineered in South London. We grew up with the sound of dub sound systems and reggae, that sonic influence resonates through all subgenres of rhythmic music from drum n’ Bass to Dubstep and beyond. Technological change brought about a democratization of creation in the sense that it became possible for everybody to become creative with minimal resources. Electronic dance music has been in our back locker ever since Compulsion our first single, rhythm has always been Test Dept’s mainstay alongside experimentation with electronics and found sound but we prefer to be more diverse in our output. The only constant is change.

—How has futurism and dadaism influenced the band?

—Paul Jamrozy: It is true to say we have many artistic influences going back to the art movements in the early part of the Twentieth Century. These movements and the art produced was indeed revolutionary and critical of the society it evolved from, using art as a vehicle to expand horizons, or to create visions of a new world of possibilities.

We found the energy and vision of these art movements inspirational. Our dockland surroundings signified the inevitable consequence of the destruction of the heavy industry and manufacturing economic base in favour of a service economy. “Use your environment” became our mantra; our utilization of societies debris, of industrial waste, our development was born from necessity but we were reflective on this. Dadaism, Russian Constructivism and Futurism were all inspirational influences that fed into our developing artistic practice, which was essentially collective and therefore manifestly anti-capitalist.

—In 2014, the book Total State Machine was published with some interviews and diaries of the band. How did the idea of writing/compiling this book?

—Paul Jamrozy: We had been exploring our archives and looking at the possibility of reworking some of our recordings, but had always had the idea of turning all the photographic images, sketches, notes, diaries of tours and amazing anecdotal writing into a publication. We met with Peter Webb who was starting up a new publishing company PC Press and he was really into the idea of backing the book project. So the idea was born and it continued to grow as we contacted people we had worked with over the years and gathered their amazing stories. These texts were placed alongside more theoretical pieces that contextualized the work and framed it in within the historic, political and cultural context of our times.

—The band returned with the film installation DS30 commemorating the Miner’s strike mentioned before. Can you tell us more about this installation? The band has been involved in other installations, right?

—Graham Cunnington: DS30 was commissioned by Rebecca Shatwell and the AV Festival in Newcastle in the north of England, an area that was the at the start, and the heart, of the UK coal mining industry.

— From TSM: Three of the original members of Test Dept joined forces in 2014 to present DS30 at Dunston Staiths on the River Tyne. The largest wooden structure in Europe reactivated in a cinematic, light and sound installation, expanding the history of this and the regional industrial landscape. DS30 marked the 30th Anniversary of the Miners Strike and the aftermath of the bitter and violent dispute between the National Union of Mine workers and Thatcher’s Conservative Government.

—Paul Jamrozy: It has been described as “a political collage…best seen as a weaponisation of memories and archives, a mustering of resources for a struggle which could be resumed at any moment. (Mark Fisher, The Wire May 2014) We have always created large-scale site-specific performance, although I prefer the term ‘location responsive’: from our very early shows such as ‘The Unacceptable Face of Freedom’ in Paddington, London in ’86 and “Our Finest Hour” at EXPO ’86 Vancouver, Canada, “Demonomania” in Valladolid, Spain, on to “Gododdin” with Welsh theatre company Brith Gof in the UK and Europe1998-90; and finally to “The Second Coming” in Glasgow for their year of Culture in 1990.

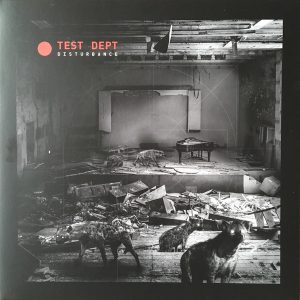

—Disturbance is your album from 2019. Do you think that it’s the perfect mix between the modern Test Dept and the ones from the 80?

—Disturbance is your album from 2019. Do you think that it’s the perfect mix between the modern Test Dept and the ones from the 80?

—Paul Jamrozy: Disturbance began as an exploration and investigation, reinterpreting our previous work and building on that foundation but we are in a completely different situation now. We thought it was timely to express how we felt about the state of the world around us, and touching on how it got to be this way. While the development of it grew organically, we always had the aim of creating a sound that was new and of the present time while at the same time referencing where we had come from. We felt it important to link the past with present in recalibrating our sound and overall aesthetic. Working with more recent collaborators, producer and sound engineer Lottie Poulet, drummer Zel Kaute, David Altweger on the visual side of the project and our newest member, Greg (Gergely) Konrady, gave us a new dynamic and fresh inspiration.

—Do you think that the situation in England is now worse than in the eighties?

—Paul Jamrozy: Yes. it certainly continues to worsen for most ordinary people, the gap between the wealthiest and poorest citizens continues to widen, with more deregulation on the way now under Boris, it is difficult to see how things will improve in terms of public services, housing, wages and working conditions. The country is very divided, a lot of people have been manipulated into believing that Brexit is about “taking back control.” In reality we are being sold out to a potential Trumpian free trade nightmare.

Hopefully, from the chaos, there will eventually emerge a shift to a bigger world-view, which looks to tackle critical issues of poverty, corporatism and climate change and address the real causes of today’s imbalance. It will take a concerted effort by those who oppose the current direction, but we need to speak truth to power, protest where necessary and elect those who will commit to driving through these positive changes.

—What is Dept Test preparing for the future?

—Paul Jamrozy: Things evolve and change as society changes around us and we are open to profound change rather than conforming to the status quo, as it exists.

We look at disturbance on a sonic as well as physical plain, as a commentary upon and an instigator of seismic social change. A reflection on the dramatic times we live in, and a warning against catastrophe through historic repetition.

—What can we expect of your future concert?

—Graham Cunnington: We use a frame built from scaffolding and hung with various metal and percussive objects, and with contact mikes built into old tyres, which trigger various samples and loops. We also have live drums and various electronic devices, which feed into the mix.

—Paul Jamrozy: Our new members have given us new energy and focus. In some ways it is a return to a harsher sound of our industrial roots mixed with more live contemporary electronics, these include an audio reactive visual mix that embraces archive and new footage, along with a pulverising dubbed up PA mix from the FoH desk. We have embraced both software and hardware electronics and tried to link them into the live percussive set-up, which still uses cast-off materials from our surroundings, in a new format. We feel the new performance brings a strong echo of Test Dept at their most forceful best.

If you still want more info about this band, here are some useful links: