Few artists have surprised us lately like Philippe Laurent, French electronic music pioneer who, when we were exchanging stickers, he was doing the same but with his auto-produced cassettes of what would later be called minimal wave. Using both his name of his Hot Bip moniker he has created very interesting works since 1979 in a sonic adventure that still has a lot to say.

—When did you start making music and what inspired you?

—When did you start making music and what inspired you?

—If I remember correctly, I started with an electric guitar in 1975 and then I got my first synthesizer in 1976, bought on credit. My first serious recordings date back to 1979.

It’s difficult for me to define my influences because they’re really eclectic. I listened a lot to the music of Pierre Henry, Pierre Schaeffer, Iannis Xenakis, Béla Bartók, Erik Satie, Kraftwerk, Heldon and Robert Fripp, of course, but so much more. As a teenager my tastes were already diverse, I loved the sound of T-Rex’s guitars, Slade’s proletarian rock, the finesse of the arrangements on Bowie’s Hunky Dory album or the cyclical movement of the strings in Debussy’s La Mer.

There was also the impact the discovery of Kasimir Malevitch’s Suprematism and Luigi Russolo’s “L’art des bruits.” The noise of machines during my youth in the factory also left an imprint on my work.

—Hot-Bip was first the name of your project before it became the title of one of your tapes, wasn’t it? What’s the story behind that name?

—No label really corresponded to my music, and reviewers never knew where to classify it, so in the early  ’80s I started using that expression to describe my music. Hot-Bip defined my musical genre, my artistic approach, my paintings and my performances, and also served as my band name when there were many of us on stage. It allowed me to escape a too restrictive classification, “not to resemble, to seek distortion.”

’80s I started using that expression to describe my music. Hot-Bip defined my musical genre, my artistic approach, my paintings and my performances, and also served as my band name when there were many of us on stage. It allowed me to escape a too restrictive classification, “not to resemble, to seek distortion.”

—Why did you also start releasing albums under your own name?

—Even in the 80s compilations the labels were already using Hot-Bip or my name. Often, foreign labels prefer to use my name, it’s “So Frenchy.”

—I read that with the help of an electrician, you built an experimental sequencer. Could you tell us more about it?

—The possibilities of the cheapest SQ10 Korg sequencer I was using at the time seemed too limited. I needed longer and more complex rhythm lines, so it occurred to me to design my own sequencer.

With an electronics engineer, we built a machine that was more than a square metre by about 50 cm deep, quite untransportable for concerts but useful in the studio. It was a kind of wooden box painted black, with a handmade and deliciously bizarre appearance, filled with pretty electric cables of all colours 😊. I used it with two MS20 and one MS10.

—On the limited cassette Réalisme Décoratif, we find the first tracks from 1979, and others recorded in 1981 and 1982. Is this an unofficial compilation? Your sound was a bit more industrial at the beginning, wasn’t it?

—It’s a C90 cassette released on the Medicinal Tapes label in the middle of the ’80s, I think. It’s hard for me to say if the sound is more industrial on these tracks. I’ve had every label in the ’80s, industrial, cold-wave, new wave, after-punk, minimal, electro-rock, techno-pop, experimental, then neoclassical in the ’90s. You pick the qualification. I prefer Hot-Bip 😊.

—Another compilation from this period was released under your name and was named Hot Bip in 2011 by the Minimal Wave label, recognizing you as one of the pioneers of the genre. What other artists were doing a similar kind of thing in France at that time?

—Another compilation from this period was released under your name and was named Hot Bip in 2011 by the Minimal Wave label, recognizing you as one of the pioneers of the genre. What other artists were doing a similar kind of thing in France at that time?

—I wouldn’t say similar because it seems to me that our music was quite different from one another, despite common points such as the use of synths and often drum machines.

Maybe “Deux” and “Stéréo” sounded more pop for example, “X-Ray Pop” more psychedelic, “Die Form” more experimental. Other examples can be found by exploring the Minimal Wave label’s catalogue.

It is this eclecticism that made the charm of the cassette compilations of the ’80s. One could find the tortured synth pop of Ptôse as well as the radical noisiness of Vivenza on the same cassette. The specialization of labels that followed closed some doors.

—Finally, another compilation called Cassettes was released in 2015 by Serendip. Do you have any material that you have not yet published?

—Yes, there are still some songs from the ’80s on 4-track tapes but I don’t have the tape recorder to play them anymore. I’m now much busier with my new compositions.

—Hot-Bip has appeared in many compilations, such as Sex&Bestiality (Cassette 1 and 2), I Spy My Little Eye, Émergence du Refus Volume 3, Mail art Manifest, Dead things, or Europa ½: France. How did you manage to appear in so many compilations? How were you contacted at the time?

—The underground scene was very active and we exchanged a lot of tapes and mail art by mail. After the first appearances of my music on cassette compilations in the early ’80s, I received a lot of invitations from abroad to participate in other releases by small independent labels. As far as I’m concerned, all contacts were made by mail. I’m rather a loner, so this means of communication suited me very well.

I remember that one of the most interesting aspects of releasing these cassettes was to discover original and undefined music, unfortunately unknown to the general public.

—In 1986, you had the vision to create the Hot-Bip Collective. What happened?

—At that time I was exchanging with a lot of artists abroad and in France through audio cassettes and postal art. So the desire came to me to create an interdisciplinary collective to create common creations with all the artists and musicians I was in contact with. I first succeeded in organizing an exhibition of the Polish artists of this collective. I had brought these artists to France in 1986 for an exhibition, which was not an easy operation because the Berlin Wall had not yet fallen. Then I had the project of producing a magazine presenting works by the members of this Hot-Bip collective, but the project did not materialise due to a lack of financial means, a recurring problem encountered throughout my career. I had so many international contacts that mailing became too expensive. So I was later forced to give up this collective design and mail art.

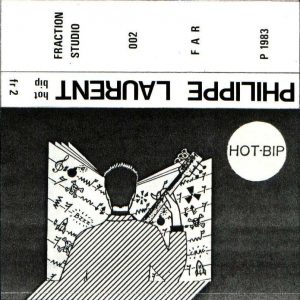

—The first tape under your own name, Philippe Laurent, is called Hot-Bip and was published by Fraction Studio. Nowadays, we would call the sound minimal wave. How did you decide to move in that direction?

—Very logically I think since I was attracted by the originality of electronic sounds and by sound experimentation. It was mainly about trying to escape from musical stereotypes, to create my own sound universe. Making this choice at the end of the seventies provoked most of the time the hostility of the musical milieu and the incomprehension of the audience, especially in France.

—Very logically I think since I was attracted by the originality of electronic sounds and by sound experimentation. It was mainly about trying to escape from musical stereotypes, to create my own sound universe. Making this choice at the end of the seventies provoked most of the time the hostility of the musical milieu and the incomprehension of the audience, especially in France.

—In 1984, the evolution of your music continues with Système Clair and takes a more of an electro turn. How would you describe your evolution these last years?

—The track “Système Clair” was recorded in 1982, and only released in 84. The discrepancy comes from the fact that I had a lot of trouble finding interested labels to produce my music apart from compilations.

I don’t have the impression that there has been deep breaks in my evolution over the years, rather a permanent sound research, varied experiences based on the same musical writing.

—The following reference is a live cassette dating from 1984, recorded at the Salle des Tanneurs in Tours. Did you give a lot of concerts in the ’80s? Could you tell us more about these concerts?

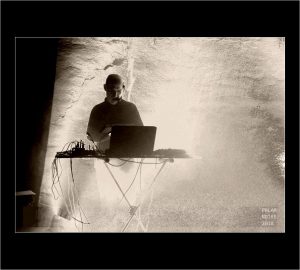

—It was Michel Madrange from Fraction Studio who came from the Paris area to record this concert in Tours. On stage the painter Mino D.C. was painting on big tarpaulins while we were playing. There were also image projections and other visual interventions if I remember correctly. I didn’t give many concerts at that time, I conceived each concert as a unique sound and visual artistic performance. They were often scenography mixing visual arts and music.

—Kunstausstellung (1985) is much more synthpop. The curious thing about this first album: you use mainly the same name for most of the songs, and only change the number. Did you want to create a certain continuity or unity?

—Yes, because at the beginning, the songs entitled “Exposition” 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 were intended to be used during my art exhibitions. I then performed these pieces on stage in the ’80s. I play them again today in concert in revisited versions.

—Fraction Studio released a lot of your records, and you were the first artist released by them. What can you tell us about this label?

—It was one of the most adventurous labels of that time, very crafty but very active. We had a lot of correspondence and artistic exchanges. Fraction studio produced some very unusual artists such as elephant, D.Z. Lectric, Bill Pritchard, In Aeternam Vale, Bocal 5 or No Unauthorized. The label still exists and regularly releases compilations.

—In the Nimramicha compilation, we find your last reference from the ’80s. What did you do up until 1993?

—I wasn’t just doing music at the end of the ’80s, I also worked a lot in the design field. In 1990 I moved to Paris and started working with samplers as well as synths. I wanted to introduce classical instrument sounds into my music. It was a long process that kept me busy for several years and which resulted in the release of the Faste Occidental CD box set in 1994.

—Did you record an album called Teoria for an Italian label? And another one for a Spanish label called …?

—Did you record an album called Teoria for an Italian label? And another one for a Spanish label called …?

—Yes, both albums were released in the mid-80s. I think the title of the Spanish tape was Rapido but I can’t remember the name of the label. The tracks called “Rapide”, present on this album, were originally intended to be performed live on stage. I think I must still have a copy of that cassette lost somewhere in an archived box.

—You have also composed music for the theater and for choreography. Is it different from working in other artistic spheres?

—Yes, I think it’s a different approach. Composing for theater or choreography means being dedicated to the director’s or choreographer’s work, it means adapting to their approach. It’s a question of tuning in to a dramaturgy, to concepts that are different from my personal themes.

—You made your first cassettes’ designs and also the covers/illustrations of other artists’ albums. Could you tell us more about this? You are also a painter, aren’t you?

—Yes, and since the beginning I have always tried to combine visual arts, music and scenography. It was rather humorous and scattered in the very first years, then the concept emerged afterwards. This multidisciplinary approach then led me to direct multimedia shows in the ’90s.

At the beginning of the millennium I had a studio, so I was able to paint large formats on canvas, paper or wood. For example, I had created a 40-meter long painting on paper for an exhibition in New York. The difficulty is that making one’s work known in the contemporary art world is even more complicated than in the musical arena.

I’m not enough of a calculator and am not very sociable either. What motivates me is the work, the reflection on the artwork and its creation, not the relational strategy.

—Another important change occurred in 1993 with your album Glorification de l’Électricité. There are again industrial influences, IDM, and a lot of classical music. How did you create this album?

—It may seem surprising, but I didn’t experience it as a change. Again, I approached it as a logical progression. It’s true that in this album, I explore metrics in 5/4, 7/8, or 9/8 that I didn’t use much before, of course, but my writing style remains the same I think.

What was new for me in this music composed in the early 90’s was to mix classical instruments sounds with electronic ones. Besides synthesizers, I used samplers for this work. Apart from these two samplers, I finally composed this album with very few means, an Amiga computer and only 16 MIDI channels, so the use of a lot of Program changes and SysEx. It was a long but exciting project.

—The same year, you released Faste occidental, which was, Glorification de l’Électricité with  an album of new versions called European Non-Ethnic Dances. Why did you do that?

an album of new versions called European Non-Ethnic Dances. Why did you do that?

—Faste occidental was indeed a boxed set that contained both albums in CD format. Non-ethnic European Dances featured remixes of tracks from Glorification de l’électricité. In reality it was a complete rewrite since everything had to be recomposed in 2/4 or 4/4 to make dance versions. I found it interesting to release this two-CD box set, it offered a wider musical spectrum. The cover also presented an artistic manifesto, a very Promethean text that supported the musical and aesthetic approach.

—During these years, you also performed multimedia shows. What can you tell us about this?

—These multimedia shows were the scenic manifestation of the double CD Faste occidental. The first one took place at the Élysée-Montmartre in Paris in 1994 and the second one at the Gelsenkirchen scientific center in Germany in 1996. The staging was multidisciplinary because I had brought on board all the artists and material I had been able to assemble for this adventure. A string quartet, actors, dancers, musicians, extras, technicians, and machines, synthesizers, construction cranes, a piano, guitars, robots, lighting, lasers, giant screens, I had also used virtual reality to play guitar in a trio with two guitarists in animated computer graphics.

In short, it was an attempt to create a complete work of art, somewhat in the spirit of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk or performances of the Italian futurists and Russian constructivists from the early twentieth century.

—How did the idea of doing a split with Xeno and Oaklander come about? They played one of your songs, didn’t they?

—Yes, the vinyl had on one side, my two songs from 1982 “Exposition 3” and “Rapide 1”, and on the other a superb version of “Exposition 3” by Xeno and Oaklander. The idea for this encounter came from the label Girouette (now Abstract Reality) located in Berlin at the time, because I had never been in contact with Liz Wendelbo and Sean McBride before this split and I didn’t know they were interested in my music.

—You played in Barcelona in 2014, how did you experience that? Where will you play next?

—I really enjoyed coming back to Barcelona, which is one of my favourite cities in Europe. It was a great experience to play in the beautiful concert hall of the CCCB, the city’s contemporary art center. The concert was organized by Domestica Records.

I then performed in other European cities, Amsterdam, Rome, Oslo, Vilnius, etc. but I didn’t often play in France.

Nowadays it’s complicated. I don’t do a lot of performances because tour organisers are not interested in non-formatted music…

—In the last few years, you’ve released two 12″, Mithra and Phoenix. Do you prefer this format or are we going to see a new album soon?

—Yes, I like this format because it allows you to quickly move from one theme to another. I spend a lot of time working on each piece of music, everything is written and I tweak each sound, and then I spend time polishing the final mix. Recording an album takes me a lot longer to complete. Right now, I’m finalizing a long format project called Nocturnes to be burned on CD and to be released on Schwerkraft Records. This composition required an effort of one year.

—How did you get the idea to make an album as a tribute to Heldon (Considérations inactuelles)? What do you like about Richard Pinhas’ music?

—It’s a joint idea with Karim Gabou (Airworld) from Schwerkraft Records. We each composed one side of this vinyl. We wanted to record this tribute to Richard Pinhas because he is an electronic music and the experimental use of the guitar pioneer in France from the early ’70s. We really like his music and I find it more interesting to pay tribute to a musician while he is alive rather than doing it post-mortem.

—What are your plans for the future?

—A joint concert with Richard Pinhas at the end of this year, or in 2021. As far as record production is concerned, after the Nocturnes release, I have other projects I’ve already started working on.

Translation: Joanne Gagnon