Spanish label Oráculo has recently released a compilation with a some tracks by EBM bands Sigbefia Five and Formal Defect, both key parts of the rooster of German label Impuls. This release has been quite important for Oráculo boss, Nico Cabañas, as he discovered the electronic body music with tracks like Sonic Sytem’s “X-Mas” that he listened a lot if a after club of Lloret called Red Sun. If you want to know a bit more about the label, here you have this interview in two parts.

The first part is an interview with Habet, one of the founders of Sigbefia Five, EBM three-piece that is living a second youth. They are featuring in one side of the split released by Oráculo, but they also appear in the compilation The Brutality of Rhythm Part.1 published by Mecanica, and they are still play an important role in the bags of some famous DJs of the scene.

—You met Carsten Barteczko and Sascha Bläser in a record fair, what was your first impression upon meeting them?

—Well, since we had the same taste in music, we were naturally on the hunt for the same records. We were almost the same age, liked to go to black parties and concerts, and so we felt a direct kinship.

—Did you have any previous musical experience or was Sigbefia Five your first band?

—No, I had absolutely no experience of making music before that. I was only DJing at home, and in 1990 I started DJing at pure EBM parties and hosting Depeche Mode parties. That’s why I felt a bit overwhelmed when I did my first recording session in 1989. Everything was new to me, so it was a real adventure.

—When did you start being interested in EBM? Did you also like New Beat or Industrial?

—I have had a soft spot for electronic music since the early 80s, starting with DAF, Kraftwerk, Krupps, Throbbing Gristle, SPK, Cabaret Voltaire and ending with Depeche Mode. But I was also listening to new wave bands like Bauhaus, Siouxsie and Joy Division. So, in the 80s my musical taste was quite mixed.

There were no pure EBM or electro parties at that time. I listened to EBM and New Beat as well as Industrial. I also liked the music from the techno club in Frankfurt at the beginning of the 90s. At that time, I was already open to almost any kind of electronic music! But EBM was and still is my favourite genre.

—Why did the band choose a name like Sigbefia Five?

—That’s a good question. I wanted an individual name that wouldn’t be confused with other bands. Sascha had a school friend who was born in Ghana. He had the first name “Winfried” and the last name “Segbefia”. I liked the last name very much and changed it to Sigbefia. The Five came from a band I really liked at the time, the Belgian EBM band Philadelphia Five.

—How was working with Carsten and Sascha? In the inner notes of the album, you said that you recorded the first three songs in a weekend without sleeping.

—As Carsten and Sascha had to borrow additional equipment for the recording, they were working under time pressure and against sleep. There wasn’t much time to work out the sounds and songs properly. Nevertheless, working with Sascha and Carsten was fun under the given circumstances and everything went hand in hand.

—Were you also involved in the recording of the Formal Defect songs?

—No, I was not involved in the recording of Formal Defect. But since they wanted to mix their own songs again that weekend with the better recording equipment, I was at least there to give them an extra pair of ears, so to speak.

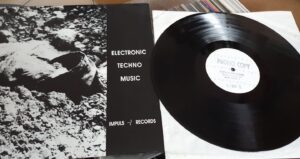

—Two of the songs of the compilation released by Oráculo are coming from the album Electronic Techno Music, the last compilation of the Impuls label. You said that you were quite proud of them. Do you think that it was here where you found your own sound?

—Yes, that was exactly the musical and sonic level I was aiming for at the beginning. My goal was that the sounds should be as individual as possible and of course the songs should be very danceable as well, which in the end worked out very well with this production.

—Why was your EP never released? Because Impuls was coming to an end? Did you try with other labels like Zoth Ommog that was quite popular at the moment?

—Why was your EP never released? Because Impuls was coming to an end? Did you try with other labels like Zoth Ommog that was quite popular at the moment?

—Impuls was already in financial trouble. This was due to management mistakes and a previous lawsuit. Sascha and Carsten then spent most of their time trying to get their new sublabel up and running, so there wasn’t enough time left to finish the Sigbefia Five LP. By the end of the year, it was already clear that there would be no more releases from Impuls the following year. The four songs that were more or less finished were pressed in an edition of 50 for promotional purposes, but unfortunately this went wrong. This meant that almost half of the records had the wrong label stuck on one side of them! After that, none of us could motivate ourselves any more for the S5 project and I withdrew for the time being and concentrated on my professional career. But I didn’t want to give the four songs to another label at that point, I was still too emotionally attached to Impuls Records for that.

—What have you been doing after this? You are currently Djing, right?

—With the end of Impuls Records in 1992, I stopped DJing in clubs. It wasn’t until 2005 that I started again and have been doing so ever since. I am a co-founder of the EBM Music Club Party and regularly play at the “Sleepwalker Night” in Cologne or other events like the Cure/Sisters parties. I even founded a small label called “Frankahdafi Rec.” in 2014 and have released a few CDs over the years. In the middle of 2020, I revived Sigbefia Five together with Carsten and Marc Tater (Synaptic Defect) and if nothing unforeseen happens in the near future, there might be some new songs soon.

—What happened to Sascha? Do you have any clue of his whereabouts?

—Unfortunately, I lost contact with Sascha after 1992. He got in touch with Carsten again at the end of 2020. However, Carsten lost contact with him a few weeks later. As far as I have heard, Sascha no longer lives in Germany.

Carsten Barteczko was one of the founders of Impuls Records and the posterior Puls-Bit and he has been part of multiple projects such as The Chemical Death, Formal Defect or the same Sigbefia Five. In this second part of the interview, we focus on his career and the history of the label.

—Carsten, your first project with a release was The Chemical Death. Under this AKA, you self-released a cassette, which was more industrial/experimental. What can you please tell us about your first steps in music? There are also some unreleased tracks, right?

—No, The Chemical Death was not my first project with a release. I founded this band together with Klaus Hahn only in late 1985. In the beginning we just did some simple, rhythmic industrial stuff with an MFB-501, a Braun CSV-60 and some electronic gimmicks. In 1986, we were joined by Michael Erren, who was responsible for metal percussion and background vocals. This led to a sound similar to that of the Einstürzenden Neubauten of the early 80s. A little later we released our first demo tape. By the middle of 1986 we had recorded a total of more than 18 songs and had even given a small concert in Micha’s garage. The unreleased material I have from The Chemical Death I will release gradually.

In 1980, with a couple of homemade sine oscillators and a multimode filter, I started creating electronic soundscapes in the style of Klaus Schulze and Robert Schröder. Later, when I got a Yamaha HS-200 and then the Roland SH-101, I recorded my compositions on cassettes for the first time, and from these recordings I made my first demo tape in 1981, which I proudly gave away to some friends. At that time, however, no one in my circle of acquaintances was interested in this kind of music, let alone that anyone had liked the demo at all. So I was surprised when I found the track “Die Erlösung” from this demo tape on VK.COM a few years ago, but it is wrongly attributed to The Chemical Death there.

—And what was C.B.M.E? You recorded some tracks with Michael Erren with this AKA around 1983, didn’t you?

—Yes, together with Michael Erren I founded C.B.M.E. in the middle of 1983. With an MFB-501 drum machine and a Crumar Stratus, we were more or less making music in style like Deutsch-Amerikanische-Freundschaft. At the end of 1983 there was a demo tape of us with about 8 songs. This is one of the few tapes that I would like to listen to again nowadays. I’ve been looking for it for a few years now, but so far, I’ve only been able to get hold of a few recordings of our rehearsals, and unfortunately they are more than just of poor sound quality. After the release of our demo, we had joined a punk band, for which I had stupidly exchanged my Crumar synthesiser for an extremely worn-out bass guitar…

—Then I guess you met Sascha Bläser and created the project Collage. How did you meet Sascha? How was the music of Collage? More minimal synth?

—I met Sascha in 1985 in Dülken, I think at a birthday party. We had, due to the common musical taste and our morbid humor from the beginning, super well understood. At that time, we both had the same goal in mind: to get out of the village we were living in and move to a big city. A year later, Sascha and I finally moved to Cologne together. It wasn’t until the beginning of 1987, after I had started working in a music shop, that I was able to afford a synthesiser again, a Crumar BIT-One. After that, I finally managed to get Sascha interested in making music. We then recorded this Collage tape with just this one synthesiser. On Formal Defect‘s Demos I+II you can hear some short excerpts of 3 of these Collage songs in the song “End Title” and yes, it’s the most extreme form of minimal electronic mixed with a big pinch of dilettantism.

—I read that after seeing a concert of industrial band SPK you wanted to do “harder” music. How was the concert and experience? Did you get into industrial then or it was already an influence?

—I read that after seeing a concert of industrial band SPK you wanted to do “harder” music. How was the concert and experience? Did you get into industrial then or it was already an influence?

—The SPK concert in Cologne was unfortunately very short, because it had to be stopped after the 2nd or 3rd song. Some of the concert visitors were very disappointed and angry about the fact that almost all the music was played only from a tape. The loud reactions from the audience caused the substitute for Ne/H/il to have a tantrum. He had then thrown one of the two metal barrels, which had previously served as drums, to the front edge of the stage, and then rammed a large angle grinder into the barrel. He had directed the resulting flying sparks directly towards the audience, which was just 1 meter away from the stage. The guests from the front rows then ran out of the club in panic, Graeme and Sinan fled into the small backstage room and the maniac then started sawing up the stage. Only the brave intervention of the club owner prevented the Rose Club from burning down that night, and no one was seriously injured. Sascha and I (and certainly all the others present) had never experienced anything like this before! We were all definitely shocked, but at the same time very impressed. Only a few weeks before we had founded a band together with the almost unknown DJ Boris Uenzen and at that time we were actually doing something more like synth-pop. But after this concert we didn’t feel like doing this project anymore. Instead, we recorded a pure industrial tape on a weekend a few days later, which we released a few months later under the name Nichtsdestoweniger via Rock’o’Rama in Cologne.

We had both been interested in industrial since the mid-80s. Especially the stuff of SPK, Lustmord, Boyd Rice and Throbbing Gristle we found more than just exciting. That’s why we had been looking forward to seeing SPK live at long last.

—After this you created the short-live AKA MASSENMØRDER and you recorded a demo. The music was more industrial, or at least the only track I managed to listen to (Who’s the buddy) is more industrial. Any plan of publishing it now that labels like Vinyl on Demand are reissuing all the industrial material of the time?

—Since neither of us currently owns the demo tape, we can’t re-release it, of course. Besides, neither Sascha nor I would be interested in it nowadays. Unfortunately, I don’t know exactly how many copies of this tape we made, but I do remember that we put the MASSENMØRDER demo together with the Nichtsdestoweniger tape on sale at Rock’o’Rama and that in the end far less than 10 copies were sold there. So if one of your readers is lucky enough to own one or even both of these tapes, please feel free to re-release them on vinyl. Sascha and I are publicly releasing the rights of use here and now!

—Finally, we arrive to Formal Defect. With this duo created together with Sascha you recorded a first self-released cassette with your demos. The sound was still quite industrial. When did you start making more rhythmic tracks? When did the EBM influence come?

recorded a first self-released cassette with your demos. The sound was still quite industrial. When did you start making more rhythmic tracks? When did the EBM influence come?

—In the beginning, the music of Formal Defect was not very different from that of the MASSENMØRDER project. Only with the Yamaha CS-40M, the Roland CSQ-100 and the Korg KPR-77, musically and sonically not much more was possible. It wasn’t until the beginning of 1988, when we had the Sequential Circuits DrumTraks, the Crumar DS-2 and the PPG 1002, that things changed a bit. But although the music was still as simple as the two previous projects, the Formal Defect Demos I+II tape sold much better. Maybe it was because of the more elaborate cover design with the inlay that this tape was finally sold at least much more than 10 times at Rock’o’Rama. It was only a few months later, after we had the opportunity to borrow some more equipment, that our style of music changed. The influence of New Beat and EBM came at the end of 1988 and was influential until the end of 1990.

—And in 1988 you, together with Sascha created Impuls Records. What was your aim with this label? Just to release your material?

—Founding an own label was actually more or less Sascha’s idea. Somehow, he was missing something like a platform for unknown bands and musicians in the field of industrial, EBM and electro music. Of course, Rock’o’Rama offered young independent artists the opportunity to sell their recordings, but unfortunately there was no support for the production of records or even for their promotion. Sascha wanted to fill this gap. At the end of 1988, he began to establish contacts with music magazines, music publishers and music distributors, and a short time later we started to build up IMPULS-RECORDS. To my annoyance, I had to leave Cologne for 18 months to do my community service. But I bought a Yamaha V-50 workstation especially for this purpose, so that I could at least make a few pre-productions and sounds for Formal Defect and Sigbefia Five during my absence. Meanwhile, Sascha was looking for new bands and artists. He visited me regularly and we listened to the latest demo tapes together and selected the bands for our next releases. So the label was neither planned nor founded just to release our own music.

—How was the relation of Impuls with other labels? Did you use to interchange material?

—How was the relation of Impuls with other labels? Did you use to interchange material?

As far as I remember, there was initially direct contact with Jochen Lange from Zns Tapes, with Sven Freuen from the music magazine Zillo, with a Jürgen whose last name I unfortunately no longer remember, and a few others. With their help we not only got more demo tapes from other musicians and bands from the end of 1988, but we were also able to release some of our songs on Zns Tapes and Aspect d’une certaine industrie. I also remember a letter from New Rose Records, but now I don’t know exactly what it was about. In general, from the beginning of 1989 Sascha had to take care of the administration of the label more or less alone. It wasn’t until the end of 1990, when I was back in Cologne, that I was able to play an active role again, and then I took care of setting up our recording studio.

—The label released three compilations: Forms of Elektronic Body Music, This is Body-Techno and Electronic Techno Music. It reminds me of the names of some Brian Eno’s albums where he is trying to define his style (first Discreet Music, then Ambient). Were you trying to find a suitable name for the style of the music you were releasing?

—Of course, we tried, but at the time it really wasn’t easy for us to categorise the music of the various bands and artists that we wanted to release together on a compilation. Not only our own songs, but also those of the other artists were mostly a mix of different musical styles. But we couldn’t and didn’t want to create a new term for a musical style or a new category. In my opinion, that was and is a task for musicologists rather than artists or music publishers.

—I guess that you wanted to fuse EBM and techno, something that nowadays it’s quite popular. How did you see the fusion back in the day?

—Not really on purpose. When new forms of electronic dance music began to emerge in Frankfurt at the beginning of the 1990s, they found their way to our ears as well. As for myself, I have always been open to everything that is new in terms of electronic music. Because we consumed this music regularly, it naturally influenced our own musical development, which we were aware of, but didn’t mind. Most Formal Defect fans didn’t like this musical change that much, though. For example, I know from one of our fans that he had left out the complete beginning part of ‘Sunset’ on his cassette recordings, because in his opinion this part destroyed the EBM character of the song…

—I guess that Electronic Techno Music compilation was a big step up with such great names as Beborn Beton, Lassigue Bendthaus and Placebo Effect. It was sadly also the last album of the label. How was it received at the time? I guess that, although now they are considered as classics, they were not that popular back in the day.

—I guess that Electronic Techno Music compilation was a big step up with such great names as Beborn Beton, Lassigue Bendthaus and Placebo Effect. It was sadly also the last album of the label. How was it received at the time? I guess that, although now they are considered as classics, they were not that popular back in the day.

—The compilation ‘Electronic Techno Music’ was already a bit of a cult shortly after its release. Lassigue Bendthaus, Beborn Beton and Placebo Effect already had a considerable number of fans back then. Sigbefia Five on the other hand was as good as unknown and Time Zone Control of course nobody could know, because that was a pure studio project of Sascha and me. Nevertheless, for this compilation there were the most pre-orders, it was sold out the fastest and landed more often on the turntables of DJs than any other release of IMPULS-RECORDS before.

—Can you please tell us a bit more about the trademark lawsuit in 1991 that made you change the name of the label to PULS-BIT?

—OK, I will try to explain this as unemotionally as possible. So, the largest German record label at the time, Ariola, ran a sub-label in the 1970s specifically for jazz music under the name Impulse. The BMG Ariola München GmbH had registered this name as a protected trademark in the field of music exploitation and had it protected in all comparative forms. Their lawyers had written to us in the middle of 1991 and explained that they could recognize a clear similarity (comparative form) between the protected brand name of their client and our label name and demanded that we not only take all records off the market and destroy them, but at the same time also demanded financial compensation in the amount of 100,000 DM, since we had considerably damaged the reputation of their jazz label with our “terrible” music. We then consulted a lawyer specialising in patent law, but he first asked us to pay him 10% of the amount in dispute before he could make a legal assessment of the facts. After we had paid him, he told us succinctly that there was nothing he could do legally and that he could only try to get a “good settlement” for us. In short, we were simply cashed in twice…

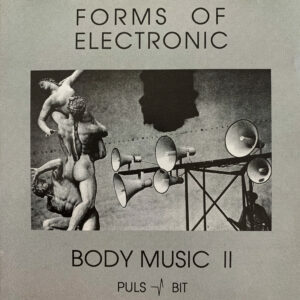

—Under the PULS-BIT label you released only one compilation, Forms Of Electronic Body Music II. Why has you stopped the label?

—Under the PULS-BIT label you released only one compilation, Forms Of Electronic Body Music II. Why has you stopped the label?

—We had already taken out a loan at the beginning of 1991 for the expansion of our recording studio. After the incident with BMG Ariola, we had additional debts and had to take out another loan, also to be able to finance the ongoing productions and those planned for this year. Unfortunately, the compilation Forms Of Electronic Body Music II sold only very sluggishly and the distribution company AMV, which had already received 1000 records of the compilation Tekkno Tanz from us, went bankrupt only a few weeks later and was insolvent. The income we had hoped for did not materialize, but the tax office and the banks still wanted their money from us. Beginning in 1992, we finally went bankrupt ourselves and PULS-BIT was history.

—In that compilation, most of the bands are you and Sasha, right? I mean Waveform, Digital Convention, Force Mission I, Section Terminated.

—That’s not quite right. Of the total of 9 bands, only 4 bands are studio projects of Sascha and me. The band Dilemma I had supported technically 100% of their production, but musically maybe less than 50%.

Due to the financial emergency situation we were already in at that time, we had replaced some well-known and superb bands, which were actually already firmly scheduled for this compilation, by 4 own studio projects for purely economic reasons. For sure, this led to the fact that the Forms Of Electronic Body Music II flopped.

—And to finish with the label, there was a sub-label called Tanz Puls, more techno related. Again, some of the tracks were also your akas. What can you please tell us about this? You wanted to move in other directions or were not interested in EBM anymore?

—Of course, we were still interested in EBM, but from the beginning of 1991 a regular income of a certain amount was required to run the label and the studio, which we could not achieve at that time only with EBM and its derivatives. As already mentioned, we really liked this “Frankfurt Techno” already in the early 1990s and in 1991 there was a bigger market for this kind of music. For this reason, we founded the sub-label TANZ-PULS. In the beginning, Sascha went to Frankfurt regularly to get in touch with other labels, artists and music producers, while I had meanwhile started to produce some songs for our first release on our sub-label. After less than 2 months we had completely finished the entire production of the compilation ‘Tekkno Tanz’ and already released it. After that, together with Kurt Mill, I produced a modern version of his timeless 80s classic ‘Filmmusik’, which was actually supposed to be released as a 12″ maxi on our new sub-label. But what Kurt and I didn’t know at first was that he had already assigned the complete rights of use for this song when he released it on the Originalton-West label in 1982. When we then contacted Matthias Becker for clarification, Kurt unfortunately also had to find out that his “friend” Matthias years ago had sold the rights of use to all his songs released on Originalton-West to Bernhard Mikulski from ZYX RECORDS. For legal reasons, I can’t tell what we experienced then with ZYX afterward.

—What have you been doing after this? You are still composing music, right?

—After that, I was not only financially ruined, but also psychologically. I got a strong depression and lost my interest in making music for a very long time. It was not until seven years later, after my brother had made contact with Kewer Video Productions in Düsseldorf for me, that I started to get in again. Thanks to my passion for industrial music and my experience in creating soundscapes, I was commissioned to produce the soundtrack for a promotional video for a metal foundry. Until 2010 I did a few more productions in the field of techno and goa and since 2020 I have been releasing electronic post-punk, EDM, minimal electronic, industrial and also soundscapes on the internet under various pseudonyms.