Our interview with John Lydon was quite accidental as our seven-months baby woke up in the middle and we had to take care of him. At least, this made John said some words that really changed our way of seeing him and that, I think, are a perfect introduction for this interview: -“It’s absolutely fine because that little baby is our future, right? And babies come first. I understand that. You know, people don’t expect Mr. Rotten to be talking family values, but I cherish the young. I’m one of the very few people in life that don’t mind children screaming on an aeroplane because when I was young, I remember how the air pressure used to hurt my ears. And so, I feel for them. I have that immediate connection”.

John Lydon and his band, PIL will be presenting their new album, End of World during three dates in Spain: 20th in Madrid, 21st in Barcelona and 22nd in Bilbao.

—How is life in Los Angeles lately? You have been living in California for a few decades now, do you like living there?

—How is life in Los Angeles lately? You have been living in California for a few decades now, do you like living there?

—John: Well, why should I not? I moved to California because of my childhood illnesses, I’m very, very prone to bacterial and throat infections. And mold is very predominant in Britain, particularly in London. Since I’ve moved here, I don’t have any of those problems. So, my singing voice is better than ever. And I love California for that. Although, yes, it has smog issues, but I live just outside of town. And I live on the beach where I go surfing.

—What was your idea when you created PIL? You said that you wanted it to be a kind of company, that’s why you added the Limited at the end, can you please tell us more about this?

—Well, we weren’t going to just be doing music. We had very, very serious, big ideas, probably above our station at that point. It’s a fabulous idea and it continues to this day in one way or another. It’s not just music. There’s artwork involved. We do our own videos now. We’re completely independent of what we call the Shitstem, which is corporate record labels. That took me years and years to challenge, to get off those things. I found independent methods to raise the money like when I did I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of here. Or the infamous butter campaign, which raised and did absolute wonders for the British dairy industry. It raised their profits by 87%. That’s not bad for a rebel, isn’t it? But with that money that they gave me, which wasn’t astronomical, I could buy myself off the record contracts and Public Image is now an independent label who answers to no one but itself. And this is why for the last three albums, it’s the same members, because we’re not divided by record company issues. We only have each other to blame and only each other to praise. It’s wonderful. It’s like a family. Rather than being part of an industrial complex. The dictates you get from large, large record labels are unbearable.

And those things earned me the title of difficult to work with. Yes, of course I’m difficult to work with if you tell me what I should be doing, because as a musician, singer, whatever, I’m trying to tell you the truth, my truth, my experiences… our truths, our experiences. We cannot do that by record company committee decisions. And so, I label large record companies, in a very polite way, “death by committee” because they make decisions about us that we’re not fully cognizant of. And then, that order is given to us. And if we don’t obey, the money is withdrawn. Well, now we control our own purse strings. We finance ourselves with live gigs, and we make enough money to go back into a studio and record a new album. It’s the wheels of industry going round and round, round and round. Self-sufficient. It is possible, it won’t make you extremely wealthy, but you will have such a wonderful life knowing that what you’re doing is right and you are a slave to no one. Yeah. Is that an answer good enough?

—Yes, of course. Let´s continue with the interview: how did you go from something more “basic”, “more rock n roll” to the experimentation of PIL? It´s something that people are still discussing how the first punk generation moved to different styles.

—I’d never, ever thought the Sex Pistols as rock and roll. Oh, no, no, no. In fact, what I stated when we first started in that band, it’s that we were the death of rock and roll. We absorbed the ideology of Do It Yourself. Rock and roll had become, and probably always was, a very, very, business structure and one that people like us would naturally feel alien to. Being working class, my natural instinct is to not work for a corporation. The voice of true rebellion. The music may sound like rock and roll at times, that’s a good thing, but it’s not rock and roll in its approach. This is not to hoodwink you into believing the world is a better place. This is music to tell you exactly how we feel about things, and it’s very nice if you agree with that, and it’s even better if you don’t.

I come from a universe where some of my best friends completely disagree with everything I have to say, and I love them for that because life should be a learning experience. And what we must never do as human beings is allow ourselves to be divided. It’s not us versus them, it’s us. And we have to work this out and stop being manipulated. Be no one’s cannon fodder.

—You have said repeatedly that you wanted to show your emotions with PIL. Let´s talk about some of them:

Pain. I guess that was the main one in your song “Death Disco”, that was composed thinking on your mother. In this moving track you sing “Words Cannot express”. Do you think that you managed to express your pain with the song? I guess the situation has repeated with “Hawaii”.

—I tried to and yes, it’s a similar approach. There was a band called Tears for Fears and they put out a record called Shout. I was really pleased for them and very glad to have met them because that’s a philosophy I adhere to, that you cannot hide emotions. You need to express them. Not in a violent or volatile way, but in an open and honest one, because many a time you might find out that what you’re feeling is wrong, but it can also be right. Yes. It’s a song about the death of my mother, which as the years evolved, performing it live also had to include the death of a few of my friends from silly heroin overdoses the music industry is rife with, and also the death of my father. And now, sadly enough, the death of my wife. It’s a song that will permanently evolve. But I’ve got a special place in my heart forever for my lovely Nora. And that’s hence the song “Hawaii”.

—Fear. You have talked about how tough was school and later all the problems and fights that you have during your Sex Pistols period. Do you think there is a sense of fear or uneasiness in your music?

—Fear. You have talked about how tough was school and later all the problems and fights that you have during your Sex Pistols period. Do you think there is a sense of fear or uneasiness in your music?

—Yes, I would hope so, because these are valid experiences I’ve had to endure and I expect the same from other songwriters, to tell the truth of what it is they’re going through. That’s why I love books. I love authors that share their truth with you. You might not agree with them, but it’s thrilling the insight into how human beings work and how different we all are, yet similar in our needs and dislikes and likes. You have to bare your heart. And live performance is sometimes like “Death disco”, extremely hard to do because I will be in full tears. I can’t help it. I can’t hold back those emotions. They become very real for that moment on stage. And I see that very seriously in the audience’se eyes. I love to be able to see who’s in the crowd and I share eyeball to eyeball contact with them. It adds. It’s the audience as a fifth member of the band, sharing their tragedies and their joys with us. So, in this respect, yes, Public Image is a bit like a church without religion.

—You sing “Anger is an energy”, even called one of your books with that sentence. In the song “Public Image” is there a bit of anger against the way people see you? or just disgust?

—No, it’s just factual that, transitioning from the Pistols into Public Image, there was an awful lot of very negative journalism telling me that I had no right to be different or to advance myself, that I had to stay in this neat little pocket that they’d decided to put me into. And so, I expressed that in a song. And yeah, anger is an energy is a concept that comes back to when I was seven years old. I had meningitis and I was hospitalized for a year. I lost my memory, etcetera, etcetera and the doctors advised my parents to keep me angry and said that that would give me the energy to bring back my memories. It worked. So, the concept “anger is an energy” has always been with me and the chance to use it in a song, years and years later, was wonderful. You must have patience as a songwriter. You can’t throw it all out at once. You have to wait for the right moment, the right tone, the right rhythm, the right beat where it fits its purpose most.

—Happiness.

— Happy penis? Yes. I’m very glad I have a penis.

—Ha, ha. When would you say that John Lydon has been happier in life?

—You can’t come at me like that. I’m generally a happy, go lucky person. I’m not one to wallow in self-pity or misery or any of that nonsense. I have to get on with things. I have to endure the pain. And in an odd way, sometimes being able to do that, to conquer tragedy is happiness in itself. I’m happy to be alive, frankly, and the gift of life I love more than anything. I don’t know where life comes from, but I’m eternally respectful for it. It’s a wonderful, amazing thing and often ignored. What a pity, silly people.

—Let’s talk about one of my favourite PIL’s albums. Do you think that Flowers of Romance has been an influence for Goth music? with all these tribal drums and all the darkness?

—I don’t know. I’m sure there was Goth going on around us at that time. It’s not about those things at all. It’s actually about a school journey that I had to endure when I was young. We went on a geography expedition to Box Hill, which is near Guildford, a part of England, and we had to study map making. But I much rather went and found the local pub and drank ale rather than study where the Romans used to plant vines to grow for wine. That was the basis of that song. And then it shapeshifted into other things about dictatorship, Nero and how easy it could be to confuse myself and believe that just because I’m a singer in a rock band, I’m better than anybody else. So, it’s self-depreciating. It’s self-criticism of a song. Especially important that every now and again you check your ego. I’m blessed because I have family and friends that will not let me get away with anything.

—Do you think that your time in jail was an influence for that record?

—Being locked up and facing a sentence of years of prison was an influence, yes. As soon as I won that case, I immediately flew straight back to London from Ireland and went into the studio. It was exceedingly difficult because I couldn’t get my band to be involved. The drummer had to go on his own solo tour and everybody else had vanished. So, it’s practically a solo record. But that wasn’t a choice. But it was good for me to mess about with saxophones and violins and drum loops and just reinvent things. And of course, my favourite sound of all is discordancy: harmonics, sonorous rhythms and all of these things I thought I could achieve by simply putting metal ashtrays on piano strings.

I’m chaotic at heart. And so, it’s in all those drones and tones where I really am. The actual notes you hear, they’re fine. But I’m up there. I know where heaven is. And it’s in those glorious unheard notes or mostly felt.

—”Francis Massacre” was inspired on that, right? Mountjoy was the name of the jail, if I am not wrong.

— There were a few prisoners there that considered themselves innocent, and they wanted me to somehow get the message out. And so, I used that song as the means. It’s basically a letter of “I’m here for life, please help me”. And I thought the screaming and the volatility in it, the ridiculously fast-paced beat were perfect for the tension that I was feeling myself while into Mountjoy.

—What do you think of Commercial Zone, the album that Keith Levene released at the time of This is what you got… This is that you need.

—I had trouble with Keith running off and doing things like that. I’ve had trouble with Wobble doing things like that. They weren’t considering themselves as band members, but thought they had privy to take tapes and make their own stuff out of it. Very selfish attitude. And they bore no sense of how much that was costing. And so, I had to not work with those people. Because that’s criminal to my mind, like a bit of thievery going on.

I quite kindly enough, give them careers and they turned their nose up at me and went off to do solo projects. That was very selfish.

—In Album you had Steve Vai playing. Why him? Do you think that it worked on the album? Was an idea of Bill Laswell to collaborate with him?

—In Album you had Steve Vai playing. Why him? Do you think that it worked on the album? Was an idea of Bill Laswell to collaborate with him?

— Steve Vai, he is rather an absurd guitarist. A thousand notes a minute. But he was around and so there it goes. He changed his style a lot on Album. He’s featured very, very predominantly, and he came up with some wonderful twists. I think he learnt really how to play rhythm guitar on Album. My original band for the record, they were too young. It was a nice idea to work with them, but they couldn’t cope with the pressures of a recording studio, let alone the endurance course of having to rehearse the songs before you go into a project like that. It was lack of experience and I know they learnt from it. We’re still friends, by the way. All of us.

—Do you like Abum in general? Do you like the result?

—It’s exactly what I wanted to do at the time. Yes. Each piece of work I’ve ever done is appropriate to its time. It has a historical accuracy.

—You told in some interviews of the importance of reading in your education and said before that you loved books.

—Yes, very much so.

—Can you recommend us any book that has marked you?

—Well, it’s, oddly enough, a book by Muriel Spark, which was called The Public Image. It’s a very small book, but I love the storyline of the corruption of the film industry and how this main character, an actress, allowed that to destroy her marriage, destroy all her personal relationships, just to be famous. The exact opposite of what I’ve been doing in Public Image, the band. A negative inspiration can be a positive.

—And a book that you think has marked your way of writing?

— As far as books go, anything by Charles Dickens. Anything. Pretty enormous range of things I go through. But as the years have gone by, my eyesight is waning now. It’s very difficult to read and I do not like spoken word books of the internet. It’s I can never adjust to the voice. It’s softly trying to lie to me.

—Continuing with books, you have written three autobiographies; do you think there is enough material for a last one?

—As my life continues, I fully expect that’s possible. The trouble with putting those books together was the amount of work involved and, of course, being independent of large corporations. They made it even more difficult just to get a publishing deal of any kind. They’re very expensive, but they cost us a fortune to put together. They’re limited in their editions. There’s only a certain amount made. So, it’s not for mass consumption, they are for the smaller market of people that are the most interested. They can always share their copies with others because sharing is what it’s all about in the end, anyway.

—Before you told us that you used I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! as a way of raising money. How was the experience? I guess your image was never as public as then.

—Before you told us that you used I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! as a way of raising money. How was the experience? I guess your image was never as public as then.

—It was a show that I was asked to do for several years and continuously said no to. But when I eventually agreed to it, it was to raise a lot of money for several charities that I had in mind. And with that approach, I then went into it. I loved it at first. It was an experience that I’d never been through before. It’s quite literally a real jungle with very dangerous ants, insect, lizards, snakes and all manner of problems. But I quickly adapted. I learned how to make a fire very quickly. I enjoyed boiling water and collecting firewood. I enjoyed all of it. It was wonderful. Where it went wrong for me was when I noted that there were plots, there were scripts that certain contributors were going along with and therefore I said no and walked out. I don’t script. That show should have been honest and open, but it was a bit of planned drama going on. I don’t do plans. Not like that.

One of the main problems I had with I’m a Celebrity was they promised me, because I had to fly there before my wife, they promised me that they would let me know that she arrived safely in Australia. And once in the show, they refused to tell me. Nora and I were booked on the infamous Lockerbie flight. That was the Pan Am jet that was blown out of the sky over Scotland by terrorists. We missed that flight because Nora couldn’t pack her suitcase in time. But for the grace of God, we would have been murdered. And so, it was very, very important that they let me know that at least she was safe. But their refusal in that meant I was out. Bye bye. Gone. That’s not right. It’s not right to see people suffering for entertainment. And believe me, I suffered because my love for my Nora is infinite.

—In your song “Public Image”, you sing: “Somebody had to stop me I’m not the same as when I began”. How much do you think that you have changed since the beginning of PIL?

—Oh, you’d better change. That’s what life is about. If there’s no change in you at all, you might as well not exist. And change is not always for the better in a lot of people. But I think for me it is. The more I learn, the better I get.

I’m less prone to making mistakes now than I would have been when I was young. But the one consistent factor is that I try to be as honest as I can with everybody and everything, because the last thing I want in my life is to wake up in the morning and not remember the lies I told the night before. I laugh at this, but these are the principles I live by. And they are fun.

—You said that you have released few techno singles under different names. Can you please tell us more about this?

—No, because I might still be under legal issues and problems with that. This was at a time when I was still on large record labels, and they were stopping me doing what I wanted to do. So, I found alternatives under different names, and I will not admit what they are.

Because I like making music, I had to continue to do that. And the record label, refusing to release your stuff is criminal to me. So, I’d find other ways and I just found trance and dance and all of that stuff which I’ve always loved all my life to be a great outlet for me. That was around the time of doing “Open Up” with Leftfield. I loved working with them fellas, but I’ve done other work with other people. I’ve done a lot of punk records too, but I want my name out of it. All right? And it’s kind of entertaining to see a record being judged fairly rather than harshly just because my name is attached to it. I’ve been going through very serious negative periods with the music press practically all my life, just so willing to condemn everything I do. So, sometimes it’s best to use a different name. But not anymore.

—But why did you release Psycho’s Path under your own name instead of using PIL?

— Because I was alone at that time. I had no band and I had plenty of songs and ideas. And I really wanted to do that. And so, I did. Virgin America at the time promised to support my solo album if I withheld it for six months so that I could go on tour with The Sex Pistols as a reunion thing. I agreed to that. But when the Sex Pistols issue was ended, the people who were in charge at the record company were there no longer. So, my solo album got dropped. Very nice again, being lied to. As you know, my attitude about corporate business will never change. There is one exception to this. When I did the butter campaign, that was corporate. You know, that’s the British dairy industry. But they were absolutely fair, above board and generous accepting me. They wanted a bit of anarchy for butter. And how can I not laugh with them on that? And so, we did the campaign. They let me do whatever I wanted. So, I basically ran into a field and improvised with cows. And it worked. And that’s good corporate thinking. But the music industry’s not so good.

—As you said, in 2012 you started your own record company. How does it work? Do you organize everything? Do you like the freedom that it gives you?

—Yeah. I have a very good friend of mine who’s also the manager called John Rambo Stevens, and he takes care of all of that side. And we have meetings. We know what we want, and we know what we get. And as I said, the money comes from the financing from live performance. It’s the greatest, greatest thing that’s happened to me in all of my music experiences because we truly make the music we enjoy making, and there’s no one telling us otherwise. And because of that, this is why Lu Edmonds, Bruce Smith and Scott Firth and I have become such good friends. There’s no outside pressure. There’s no division. There’s no ego. There’s just a love and respect. That’s exceptional for me.

—Why do you think that the rest of the Sex Pistols did not want you to know about tv series Pistol? Did you finally watch it?

—Well, I think someone in there, because the Disney Corporation were the backers of all of this, they didn’t really want the truth. And I think that they gilded the donkey. They cut the penis off the horse. They took all the energy, the truth and the bollocks out of it and turned it into what? Just average old pop tripe. Maybe that was the ambition, to take away the challenge that was there initially. And they did a very nasty job on that. But not telling me was very, very deceptive. They gave me something like a eight days warning just after Christmas, a couple of years back, and if I didn’t comply with their wishes, they were going to take me to court, which meant that eight days later, Walt Disney’s money took me to court. And how the fuck am I going to win against that? Very unfair. At the time, they also knew that my lovely wife Nora was ill. They knew that as a fact. So, it was a very, very, very harsh time for me. And I had to go to England to fight that case in court while my wife was ill. Murderously unfair.

And it’s just sort of a personal level. How on earth can you say a documentary is real when you’ve excluded the main singer-songwriter? And image-maker and frontman. They made all those decisions to eliminate me. And I’ve got to tell you that they had three years, from what I know in advance, without telling me, to plan this out. It’s not necessarily them either, the other Pistols. It’s more to do with the Disney Corporation, some very big wig, nasty American lawyers and some very, very wicked management that they have. You know, they’ve made their bed. Let them lie in it, and lie is all they can do.

It’s horrible. But, you know, that’s life, isn’t it. You know, for a band that was so anti corporations, like The Sex Pistols. Wow! They went running straight into it.

—It really makes no sense.

—Well, it does if you felt no responsibility or connection to the songs or the image of the band, if you felt no obligation to any of that, this of course, would be the move that they would make. And so yeah, they don’t belong in The Sex Pistols history for this, period. They are the devil. Get behind me, demons! I can laugh at it because I can’t be bitter. I can’t hold resentments. It’s not my nature. It’s the pattern of life they’ve decided to take and have no say about that at all. I couldn’t care. They’ve lost my interest as human beings.

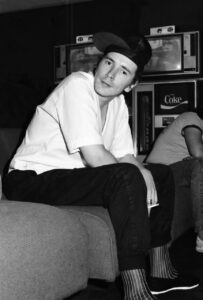

Photo: Andrés Poveda

—What can you tell us about the song “Hawaii” that you wrote for Eurovision?

—I did not write the song for the Eurovision. Let’s get this straight. The song was already written. Some Irish friends of ours heard it and put it forward to a TV show called The One Show, who then invited me to perform it live with the prospect of it being a Eurovision song. I never held any hopes for that, but the opportunity of being able to perform the song that I wrote for my lovely wife before she died, and being able to have that on TV for her to watch was a magnificent, generous offer from them. It helped my lovely wife no end watching that. She even picked the suit that I wore for it because I told her I was going on Irish television, and she just went: -“John’s, you must wear this”. So, I ended up in a pink plaid suit. Thank you. And it was very, very excellent to come back to LA and sit down and watch it together. That was a very moving, very touching part of my life. It was very hard to perform live because I knew she was going to die at some point soon. But at least had that precious moment with her. And I will love Ireland forever and everybody in it just because of that magnificent moment.

—Do you think that “Hawaii” was too deep for the contest and the general audience prefer more light material?

— I’ve no idea. I don’t know how the voting is done. It’s irrelevant. How do they make or decide what the top 30 is? It’s not based on sales, is it? I learned that years ago. There were several Pistol records, Anarchy in the UK. God save the Queen, but there was no number one those weeks. So, I’ve always known these systems to be open to corruption or possibly in error. So, none of those were my ambitions. My whole thing of writing the song and performing it was utterly and completely because I’m madly still in love with Nora, my lifetime partner, and life is hell without her. But it’s a good hell. It’s better than no life at all. Because both of us have always loved being alive. I’ve just now got to carry the rest of the journey alone. That’s all right. More song material.

—I guess it’s going to be hard to play “Hawaii” live in the new tour, especially now. Are you sure that you want to play it live?

—Not as hard if she was still alive because the expectation of imminent death was far more painful than having now to deal with her death. It’s just the way it is. And I’m sure there’s many people out there that have gone through similar and worse experiences, and the joy of a gig is that they will share those experiences with me. It’s an anthem. It’s an anthem to how to deal with tragedy in a positive way. One of the highlights of the song for me, which Nora fully understood, even though she was ill with Alzheimer, was the word aloha, which I use as a refrain over and over again, because in Hawaiian language, it means hello and goodbye. And that that is extremely poignant.

—Lately you have been doing also some spoken word tours, what can you please tell us about them?

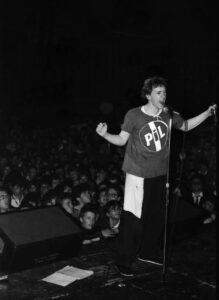

Photo: Andrés Poveda

—I love them. It’s like going to a strange pub where people sort of know you and they’re all inquisitive and they all have questions and you answer correctly, and it’s extremely good fun. It’s very chaotic, it’s disorganized, and everybody’s happy. I mean, sometimes I can break out in karaoke, and anything is possible. I have to be completely unscripted when I do it. And I love that knife edge of this could collapse and be terrible. It makes you work harder for other people. Just a wonderful thing to be able to do. Yes, I love it. It’s hilarious. Sometimes the public just break out in song themselves. It’s all unexpected. Nothing planned. Nothing scripted. Lovely. Human beings being human. The greatest gift.

—You have been drawing the covers of your albums, what´s your inspiration?

—I’ve had a finger in the artwork since the very beginning of my career because I like painting. You’ve got the element of sound and words, and that used to be enough for me, but not now. I think it’s nice to have a visual interpretation as well. The album cover is very much seriously a part of everything that’s inside. I’m using basically the colours and textures and schematics through colour to explain what the songs really mean, because colour does have an emotional effect on people just like words and just like sounds. It’s just another angle. Another thing we love to do now is our own videos, which are very much like your dad bought a new camera and he wants to film everything. It’s very home video. You got a lovely little baby there, and of course, you’re going to be filming it, right? Well, that’s the vibe. And that’s an approach I don’t think anyone in the music industry has ever thought about it. It’s where the real true emotions lay. We don’t need expensive productions. Everything is for real, no stagecraft.

—Anything that you can tell us about the new album? At the time of the interview, we have known only three singles.

—It’s 13 songs. We got through it very, very fast, like two months at most. We had to use several different studios because after the Covid lockdown ended, everybody was running to recording studios. So that was difficult. But being Public Image, we liked the faults and the different sounds of the different places, so it all paid to our advantage. As I said, there were 19 ideas which we bounced down into 13 songs, enjoyed everything of it. I’ve dealt with my personal tragedy with Nora, but that’s not all of the universe, so I had to consider many other concepts too. There’s a song called “Car Chase”, that’s about a friend of ours. The authorities in Britain decided he was incapable of looking after himself. So, they put him in a home. And of course, he escaped, you know, very much like what I would do. And I love him very dear for that. And so “Car Chase” is a song and an adoration of his free spirit.

—That was one of the first singles, right?

—I don’t know. Any order you like. What we’ve done is issue snippets of songs so that people get an advance warning of just how varied this album is. “Penge” is, I think, the first sound bite we released. That’s about an imminent Viking raiding party that it’s going to slaughter and kill everyone in a seaside village. And the alternative the children are offered for safety is to follow a Druid priest off into another harbour where they’d be safe. But the Druid priest turns out to be a child molester. Just because position A is bad, don’t jump to position B. Look for C, D, etcetera. Find more than one alternative in life and make your own decisions. Otherwise, you won’t survive.

Photo: Andrés Poveda

—What can we expect of your concerts in Spain?

—Great fun, of course. Spain’s always been fantastic. And your folk ain’t so different from my folk, regardless of what the governments tell us. You know, when you come to a PIL gig, you leave the problems of the world outside. And in our house, you be yourself. And you’re more than welcome. True love.

—I guess we will have some of the new songs and a few of the classics.

— Yeah, it’s been a long time, and it still might do some of the old ones because someone might have forgotten them. Until we start rehearsal, I can’t give you a definite list because there’s four of us and we all consider things differently.